The Colonel - a biography

The Colonel is the name we give to our single variety cider made out of our home county’s finest apple, Ashmead’s Kernel. Obviously, the KERNEL : COLONEL homophone is one reason to name it so. But perhaps there’s another …?

Major General Sir Archibald Digby Ashmead KCB KCMG served in the ceremonial position of Colonel of the Gloucestershire Regiment of the British Army, the Glosters, for a short period of time in 1902. With an optimistic and cheerful demeanour, he eschewed the formalities of the day, was an enlightened thinker and in many ways was well ahead of his time. These traits made him popular with the troops, particularly those of the 1st and 3rd Battalions but he never built a rapport with the 2nd Battalion, for some reason.

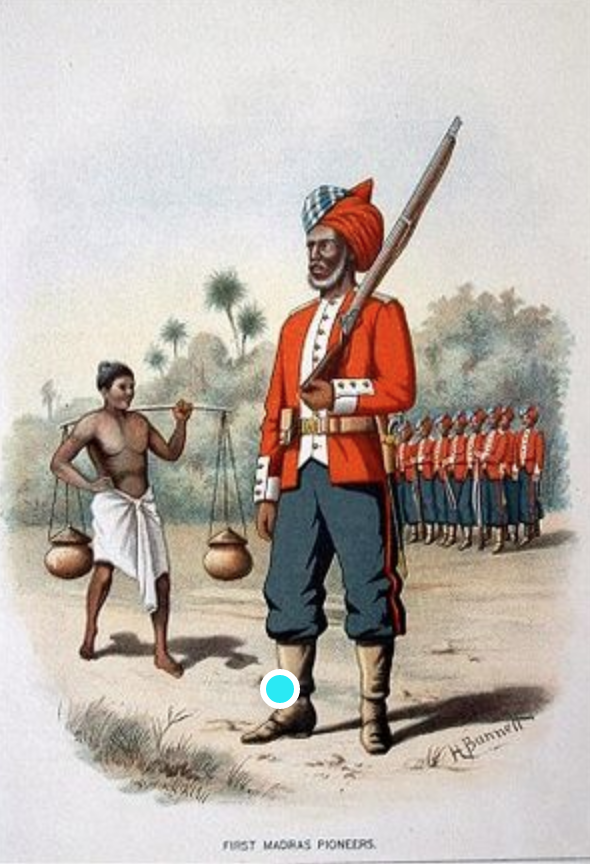

Archibald had an unusual childhood. His father, Cuthbert, was the seemingly permanent chargé d’affaires for the East India Company in the French enclave of Pondicherry (now Puducherry), from the time of Archibald’s birth in August 1838 to his retirement in the mid-1870s. Rather than send his first - and only - son back to England for the traditional, formal, staid “public” school education, Archibald was enrolled into the local académie française. Exposed to the diverse and varied influences of Pondicherry, Archibald developed a keen awareness and understanding of the people of India; he spoke both Hindi and Tamil fluently, as well as French, and gained an outsider’s perspective on the workings of the British Raj. This cosmopolitan outlook came in useful when, during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 as a newly commissioned Lieutenant in the Madras Army of the East India Company, he succeeded in quelling a potential rebellion in Chinglepet (now Chengalpattu) by quiet diplomacy and without bloodshed, largely acting on his own initiative and possibly in contradiction of orders (that never arrived, according to his defence at the subsequent Board of Enquiry). Uniquely, controversially but with foresight, he subsequently referred to the Mutiny as the First War of Indian Independence.

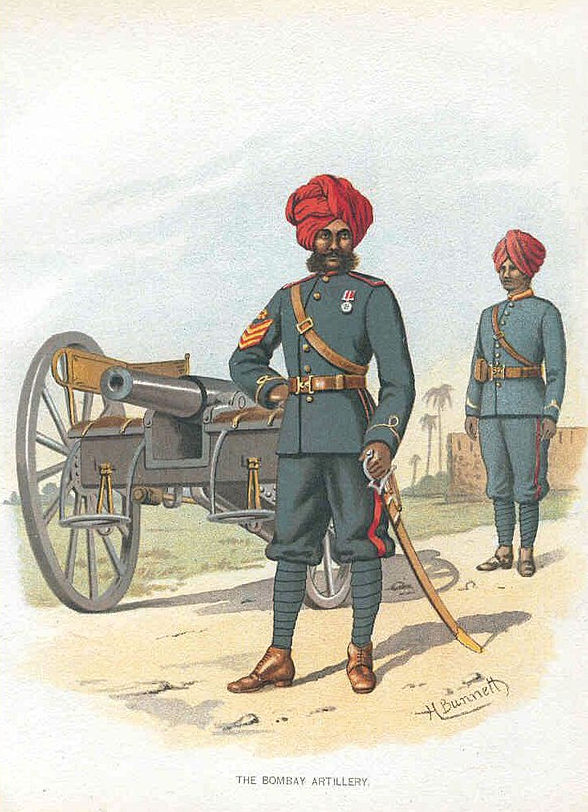

Despite being a controversial figure, his thoughtful and empathetic approach to leadership ensured that promotion followed. Seeking further notice and influence than was available in the relatively quiet southern Indian states, Archibald gained a transfer to the Bombay Army in 1868. It was here that his his love of cricket came to the fore. Deprived of the sport during his childhood in Pondicherry, he quickly demonstrated excellent hand-eye co-ordination and proved himself to be a natural cricketer. As with his time in eastern India, Archibald was at pains to understand the indigenous population and was a regular visitor to the cricket-playing Parsee community, where he learned the art of wrist-spin bowling. A useful lower-order batsman, it was his mesmeric bowling that ensured he was a regular in the Regiment’s First XI … until he bowled his Commanding Officer, Lieutenant General The Honourable Sir Augustus Almeric Spencer, GCB, for a golden duck with a perfectly flighted and well-disguised googly, in the annual intra-regimental match. Although the General took it well, the wider “establishment” felt that Archibald’s competitiveness “wasn’t cricket” and demoted him to the Second XI. Infuriated at such petty-mindedness, Archibald instead chose to play for the Regimental Third XI for the rest of his time in India and spent more time with the Parsee dominated Zoroastrian Cricket Club. It is thought that his preference for the the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the Gloucester Regiment, at the expense of the 2nd, came from this episode, although this can only be regarded as conjecture

He served with gallantry and distinction in the Second Afghan War and the Third Anglo-Burmese War. He was both courageous and considerate of his men, the antithesis of an armchair general, but sustained a serious injury when effecting a crossing of the Irrawaddy. This necessitated him being invalided to England, where he landed at the age of 50, a land he had never visited before. During his recovery he tasted an apple for the first time - the particular variety is not recorded - and although his initial reaction was one of disappointment he did, in time, come to appreciate the fruit, although it never fully replaced his love of mangoes. On recovering he joined the British Army and towards the end of his career he would always be seen eating an apple when inspecting the troops, the end result of which was mirth amongst the soldiers and a solitary apple core littering the parade ground, which the pomologically knowledgeable soldiers charged with tidying up referred to as an “Ashmead’s kernel”.

Thanks for reading these idle meanderings; you should have better things to do.