Sausage rolls, steel kegs, heatwaves and Belgians

Just about a year ago the nation emerged, blinking and somewhat hesitantly, out of its first Covid Lockdown. Quite a few of us headed straight to the pub, to be greeted with rapidly amended menus featuring the now ubiquitous sausage roll, an item deemed to be the “substantial meal” that needed to accompany a pint; a good enough reason to suspend a vegetarian diet, given that Greggs’ surprisingly good vegan sausage rolls aren’t generally available in pubs. (Our lapsed dietary habits also recently extended to the sausage roll at The Seven Tuns in Chedworth, where everything is a delight.) A year ago, we also started to resupply pubs with our cider in kegs. Steel kegs. Kegs that can be used time and time again.

A lot of cider-makers use Key Kegs, “the environmentally friendly one-way keg”, environmentally friendly because the materials are 100% recyclable. Unfortunately, recyclable does not mean recycled; as their own website says, “Every KeyKeg is made of 30% recycled material already,” which means - it’s not too difficult to read between these lines - that 70% isn’t recycled; it’s virgin plastic, or whatever else goes into them.

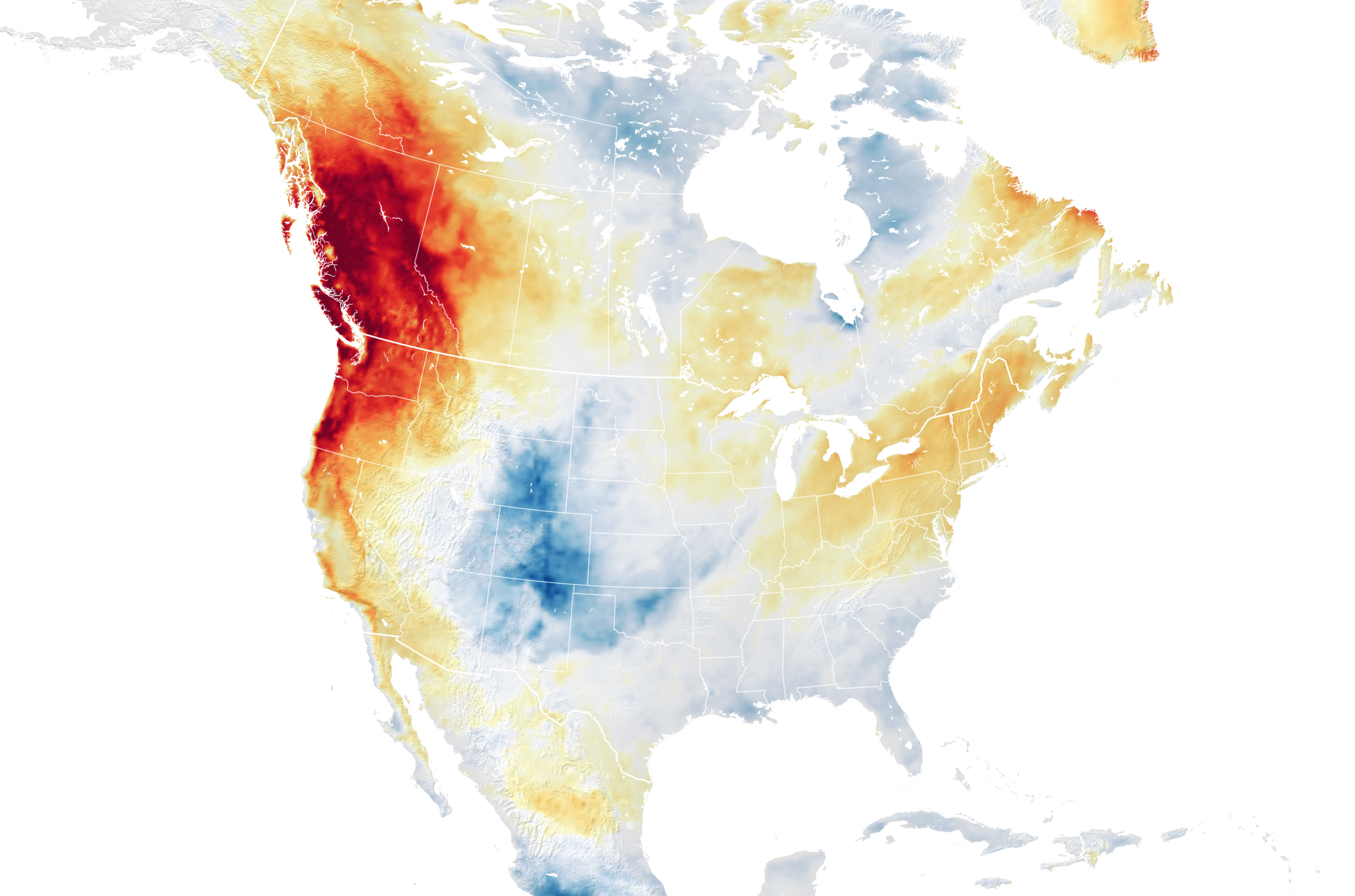

From a purely financial perspective, we’d be better off using Key Kegs. Steel kegs are expensive, either because of a high capital up-front cost, or through daily rental fees that eat through margins fairly quickly. Plastic kegs are cheaper … and that’s because the cost to the environment isn’t included within the price of plastic. That cost is paid by someone else. This year, it’s the people of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, having to endure record-breaking temperatures in the high 40s Celcius and the more than 550 excess deaths in British Columbia alone that accompanied the heatwave. Or the people of Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia who watch, bemused and helpless, as their homes are flooded and washed away. Last year, bush-fires in Australia, in California the year before. And these are just the disasters that we hear about; did Cyclone Idai that walloped Mozambique reach our airwaves? Did Typhoon Eloise? Of course, cider-makers using Keg Kegs aren’t solely responsible for global warming … it’s the result of all the decisions we make in our daily lives, either as individuals or as businesses … but our continued use of plastic isn’t helping. We all make choices.

Temperature anomaly: the darkest red zones were +15 Celcius above average, on June 27th, 2021

Whilst we do our best not to contribute to the problem, we’re not saints, either. The Apple Wagon is a thirsty, diesel vehicle, which we use to gather apples or to make larger deliveries, but use as infrequently as possible. But, in our defence, it’s an old beast. There is so much carbon sunk in building cars - in the energy used to extract the ores and make the metals from which the vehicles are constructed, to make the vehicles themselves and all their component parts - that it’s better to use an old car until it falls apart, even a fuel inefficient one, than buy a brand new car. The process of building a medium-sized car contributes about 17 tonnes of CO2 to the world’s problems. Let’s do the maths …

Assumption: annual mileage

12,500 miles a year

Old Car

30 miles per gallon = 290 grams CO2 per mile = 3.625 tonnes CO2 per year

New car

40 miles per gallon = 217 grams CO2 per mile = 2.713 tonnes CO2 per year

difference

Our old, inefficient car generates 0.912 tonnes more CO2 per year than a new, fuel efficient car. It’ll take 18.6 years for the fuel efficiency benefits of the new car to overtake the carbon cost of building that new car.

conculsion

It’s better for the planet to keep old bangers on the road for a few more years than to build new motors. The real conclusion is to reduce, to reuse and to recycle - in that order; reduce the amount of stuff we consume, reuse the stuff we do have and, as a final resort, recycle what we can’t reuse.

To repeat, we’re not saints. We do use some plastic packaging. We use plastic caps on our apple juice and our still (uncarbonated) cider. Each cap weighs 2 grams and we go through about 6,000 caps a year. A portion of the material is made from recycled plastic, a portion from virgin plastic, and the material is recyclable, but we don’t know whether people recycle them or not. We’d love to move to metal caps - still single use but more easily recycled - but right now can’t afford to tie up cash in an infrequently used capping machine.

We also sell some cider as Bag-in-Box, in which cider is filled into what is, effectively, a single-use plastic bag (the bags can be reused in a Heath Robinson sort of way but we’re not convinced it’s totally hygienic). We don’t use a lot, less than 5% of our sales, but in this instance it’s because there doesn’t seem to be an acceptable alternative. We’re looking at using steel casks, but that doesn’t seem to work from a cider quality and longevity point of view. We’ll keep exploring … and focusing more of our effort on selling cider in steel kegs and glass bottles.

Cullet … and why we love the belgians

Our favourite word of the week … cullet is broken and recycled glass used in the glass-making process. In theory, glass can be broken down and recycled over and over and over again, without a diminution it its quality, and it also takes less energy to make new glass from old than to make virgin glass from raw materials - sand, soda ash, limestone, dolomite and a few other ingredients. The problem is with contamination; broken glass gets contaminated with ovenware and ceramics within the recycling process, which does reduce the quality of the resulting glass. The UK also has a particular problem; we export huge quantities of whisky in clear, flint glass bottles and import huge quantities of beer in green bottles. The end result is that cullet from the UK’s recycling system contains more smashed up green bottles than we really need, and fewer clear flint bottles that we’d really like, so we end up having to make new virgin glass.

In the UK, we recycle about 70% of the glass we use and so, on average, about 70% of a glass bottle is made from recycled glass; the European average is 76% and number of countries have almost completely closed the loop and perfected a circular economy in glass making, where everything is reused and recycled. As usual, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Denmark are all close to the top of the league, but best of all is the country we (unfairly) tend to ignore or laugh at … Belgium … where 99% of glass is recycled. It can be done, if there’s a will. Perhaps, one day, even Keg Kegs will be made from 99% recycled plastic, at which point we may consider using them. Until then, we’ll try to make responsible choices in the way we run our small business.

As an aside - and to add some levity to proceedings - we invite you to name the Belgian pictured at the top, identify what he invented and comment on why it was such a significant invention.

Thanks for reading.